Breaking and Fixing Wiesner’s Money

This post explores how Wiesner’s quantum money becomes vulnerable once attackers can interact with the bank itself.

Wiesner's Quantum Money and Bank Access Attacks

In the previous post, we investigated Stephan Wiesner's quantum money and concluded with a discussion of its security. However, our security discussion made a strong assumption: that an adversary trying to forge a legitimate bill |$⟩ has no access to any other resource that depends on the bill.

In reality, the adversary does have an additional resource: the bank. The behavior of the bank depends on |⟩:itwillaccept∣⟩: it will accept | ⟩:itwillaccept∣⟩ with certainty, and reject any state orthogonal to |$⟩ with certainty. Does the scheme remain secure if we consider an adversary with access to the bank? That's the underlying question of this post.

Recap: Wiesner States

Wiesner states are the key building blocks for many quantum primitives, including quantum money, quantum key distribution, and quantum encryption. They will occur frequently in future posts.

The simplest Wiesner states are single-qubit ones. There are four of them, which we divide into two bases: the computational basis {|→⟩, |↑⟩} and the Fourier (a.k.a. Hadamard) basis {|↗⟩, |↘⟩}. We use |L⟩ to denote an unknown single-qubit Wiesner state, which could be any of the four states.

Recall that "a basis" is "something you can measure". If we have one of the states |→⟩, |↑⟩, we can perform a computational measurement to determine which it is. Similarly, we can distinguish the states |↗⟩, |↘⟩ using a Fourier measurement. But what happens if we, say, apply a Fourier measurement to |→⟩?

This scenario is where quantumness finally plays a role: the state will collapse to either |→⟩ or |↑⟩ with equal probability. The same holds in all directions.

To illustrate the importance of this collapse, imagine computationally measuring a Wiesner state |L⟩, obtaining the output result →. What does this tell us about L? It could be that L=→, but it could also be that L=↗ or L=↘ and just happened to collapse to →. It is impossible to tell these scenarios apart. At the end of both, we have the exact same information. This inherent uncertainty (which is mathematically identical to Heisenberg's famous uncertainty principle) is what underlies the security of Wiesner's money and other quantum primitives.

An n-qubit Wiesner state is simply a string of single-qubit Wiesner states. For example, |→↘↑⟩ is a three-qubit Wiesner state. The most interesting fact about a random n-qubit Wiesner state is that it decomposes into n random one-qubit Wiesner states.

Unlimited Cloning Attacks

The attacks we will see today do not appeal to how Wiesner's money works. Instead, they try to learn the Wiesner state |$⟩, which will allow them to make unlimited perfect copies.

Remark: To break the security of a quantum money scheme, it is enough to convert a single bill into two states that pass verification with a non-negligible probability. The attack we discuss is much stronger: it can make an arbitrarily large number of perfect copies.

An adversary that can learn one of the qubits of |⟩whilekeepingitintactcanproceedtolearntheentireWiesnerstatequbitbyqubit.Tostreamlinethenotationfortherestofthepost,wedecomposethemoneystateto∣⟩ while keeping it intact can proceed to learn the entire Wiesner state qubit by qubit. To streamline the notation for the rest of the post, we decompose the money state to | ⟩whilekeepingitintactcanproceedtolearntheentireWiesnerstatequbitbyqubit.Tostreamlinethenotationfortherestofthepost,wedecomposethemoneystateto∣⟩ = |L⟩⊗|ψ⟩ where |L⟩ is a one-qubit Wiesner state, and |ψ⟩ is the remaining (n-1)-qubit Wiesner state. We focus on an adversary trying to learn L without destroying |ψ⟩.

Lutomirsky's Attack

Adversaries with bank access were first discussed in a 2010 note by Andrew Lutomirsky. He noticed that if the bank is "friendly", willing to verify many states, always returning the post-measurement state, even if verification fails, then it could be easily attacked:

Given |⟩=∣L⟩⊗∣ψ⟩,weset∣L⟩asideandreplaceitwith∣→⟩toobtainthemodifiedbill∣⟩ = |L⟩ ⊗ |ψ⟩, we set |L⟩ aside and replace it with |→⟩ to obtain the modified bill | ⟩=∣L⟩⊗∣ψ⟩,weset∣L⟩asideandreplaceitwith∣→⟩toobtainthemodifiedbill∣'⟩ = |→⟩ ⊗ |ψ⟩, which we ask the bank to verify. We repeat this process several times (each time using a fresh copy of |→⟩) to obtain a list of outcomes, each of which is either accept or reject. What does this list tell us?

- If L=→ then |⟩=∣⟩ = | ⟩=∣'⟩. The "modified" bill is identical to the original bill, so the outcome is always accept.

- If L=↑ then all verifications fail and all outcomes are reject.

- If L=↗ or L=↘, then each verification has a 50% chance to succeed, so we will almost surely see at least one accept and one reject. (The probability that we don't decays exponentially fast as we add more repetitions, like the probability of N coin flips all having the same result.)

The first two outcomes immediately tell us L. In the third, we know that either L=↗ or L=↘, which we can distinguish by Fourier measuring |L⟩.

The |ψ⟩ part is the same in |⟩andin∣⟩ and in | ⟩andin∣'⟩, so it wasn't modified by any of the verifications.

We managed to learn L without changing |ψ⟩. We can repeat the process for the rest of the bill, qubit by qubit, to learn its entire state. Lutomirsky proposes to defend against this attack by destroying bills that failed verification. Is it enough?

To answer this question, we detour to 1993.

Testing a Bomb Without Touching It

Lev Vaidman is a founding father of fundamental quantum theory, the field that seeks to make sense of quantum causality. In the early 90s, Vaidman and his student Avshalom Elitzur noticed a causal quirk in quantum mechanics: in a sense, you can observe events that did not happen. In 1993, they published a thought experiment demonstrating this quirk through a peculiar apparatus now called the Elitzur-Vaidman bomb tester.

In the thought experiment, our task is to determine whether a bomb is live or a dud without detonating it. The only way we can interact with the bomb is to trigger it and see if it explodes. This might seem dire. But according to Eliztur and Vaidman, the situation is not as helpless as it seems!

The details of the bomb tester are beyond the scope of this post (but there are many excellent sources for the curious). The gist is that it is possible (and, surprisingly, surprisingly simple) to set up the interference so that, even if the bomb never explodes, the outcome changes depending on whether it could explode. We can tell apart "the bomb is a dud" from "we didn't trigger the bomb, but it would have exploded if we did" without ever wandering into "the bomb exploded" territory!

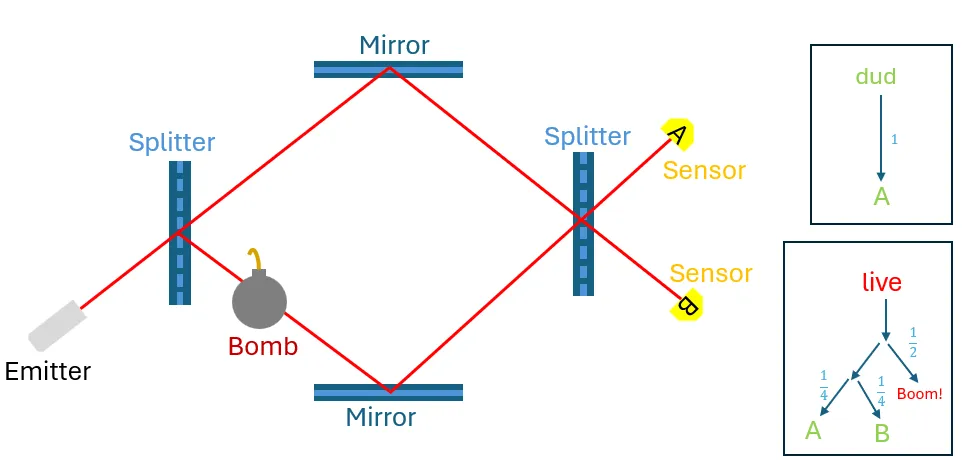

An Elitzur-Vaidman bomb-tester. The causality routes on the right show that if the bomb is dud then sensor A is hit with certainty, but if it is live and was not triggered, then A and B are equally likely.

We will not see Elitzur-Vaidman contraptions in airports any time soon. The key gap is that for the tester to work, the interaction with the bomb has to be set up in such a peculiar way that people still argue whether it is even physically possible. But testing bombs was never the purpose. Just to make a note about a reality where interactions similar to this hypothetical bomb do exist.

In 2014, Brodutch, Nagaj, Sattath, and Unruh (BNSU) noted that a Wiesner bank that only returns bills that pass verifications fits this shoe.

The Bank is the Bomb

BNSU's attack is identical to Lutomirsky's attack, except that instead of directly approaching the bank, they treat it as a bomb. To do so, they slightly upgrade the bomb tester to a bomb quality tester. What does that mean?

Say that a bomb has quality p if it explodes with probability p when triggered. Elitzur and Vaidman only considered the cases p=0 (dud) and p=1 (live). BNSU noted that if you can also tell apart the case p=1/2 (without setting off the bomb), you can learn a Wiesner state with the bank's help while avoiding failed verifications.

How? We start the same as in Lutomirsky's attack, replacing |L⟩ with |→⟩, to create the modified bill |$'⟩=|→⟩⊗|ψ⟩. But now, instead of asking the bank to verify this state, we treat the bank as a bomb and check its quality.

- If L=→ then the verification never fails, making the bank a "dud bomb", and the quality-tester will return p=0.

- If L=↑, then the verification always fails, making the bank a "live bomb", and the quality-tester will return p=1.

- Finally, if L=↗ or L=↘, the verification fails probability p=1/2.

As before, we can distinguish the same three cases, and we can now proceed as in Lutomirsky's attack. The difference is that we avoided failed verifications.

Fixing Wiesner's Money, Again

To prohibit this attack, BNSU suggest that the bank should be strict and always destroy verified bills. If the bill passes verification, destroy it and mint a new one in its place. If it fails, throw it in the bin and the forger in jail.

It is not too difficult to see why this prevents the BNSU attack: the bomb-quality tester maintains a "probe" qubit that is entangled to the |→⟩ qubit we added. The attack only works if the probe remains entangled through all rounds of verification. By constantly replacing the bill (even if verification passes), the probe becomes disentangled, and the entire attack collapse.

So this attack fails. But is Wiesner's money with a strict bank generally secure?

Conclusion

The discussion above is not just about Wiesner's money. It demonstrates how delicate uncloneability is. Relying on the seemingly robust uncertainty principle, which may seem to include built-in security margins, can create a false sense of security. Yet, even in simple examples, slight modifications to the assumptions can have dramatic consequences for security. Any attempt to implement such constructions in the real world requires reflection, care, and expertise.